Charities and the Cost of Living:

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/bucks/vol1/plate-12

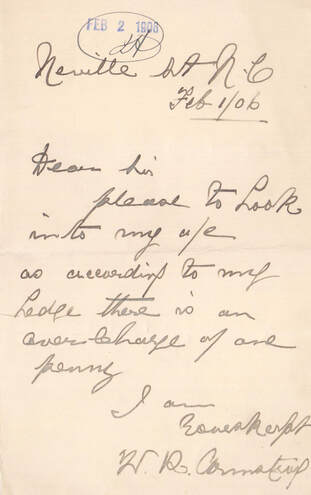

The Cost of Fuel:

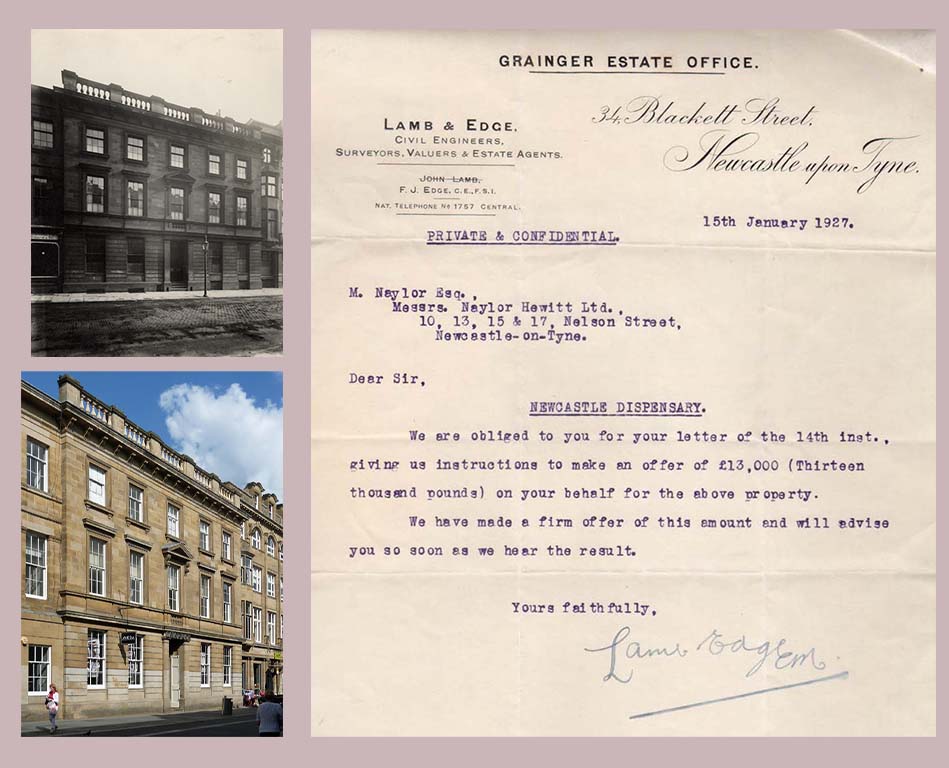

Living Conditions, Housing and Rent:

Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-SA)

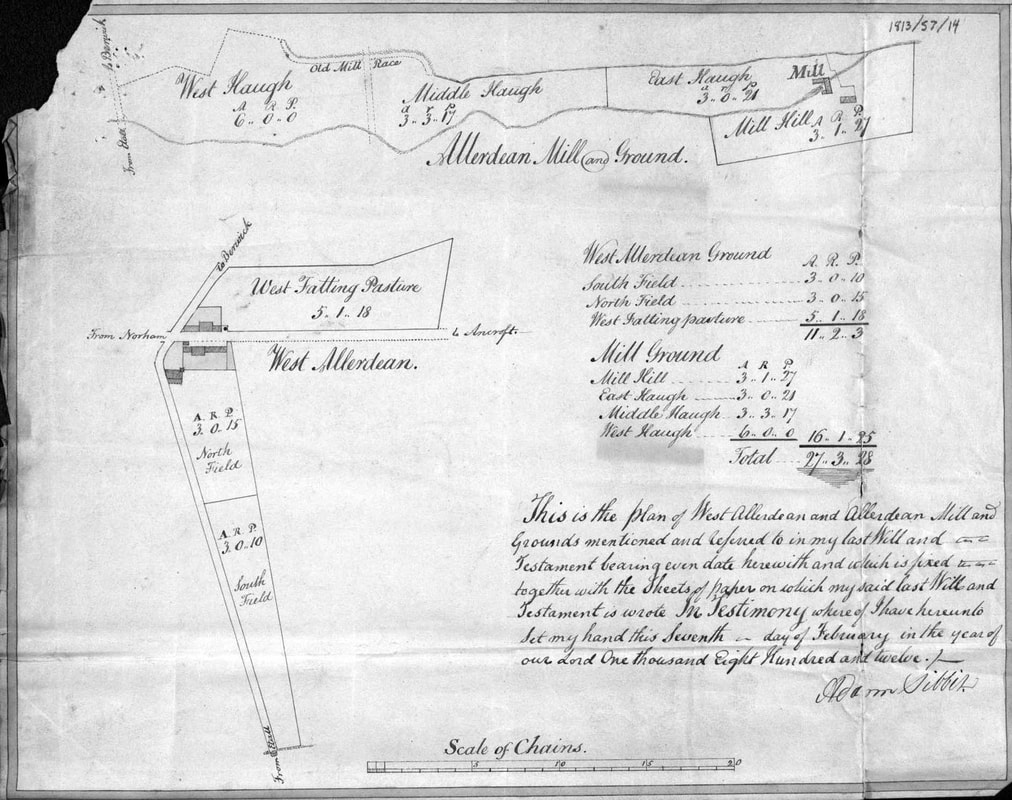

https://maps.nls.uk/view/102340217

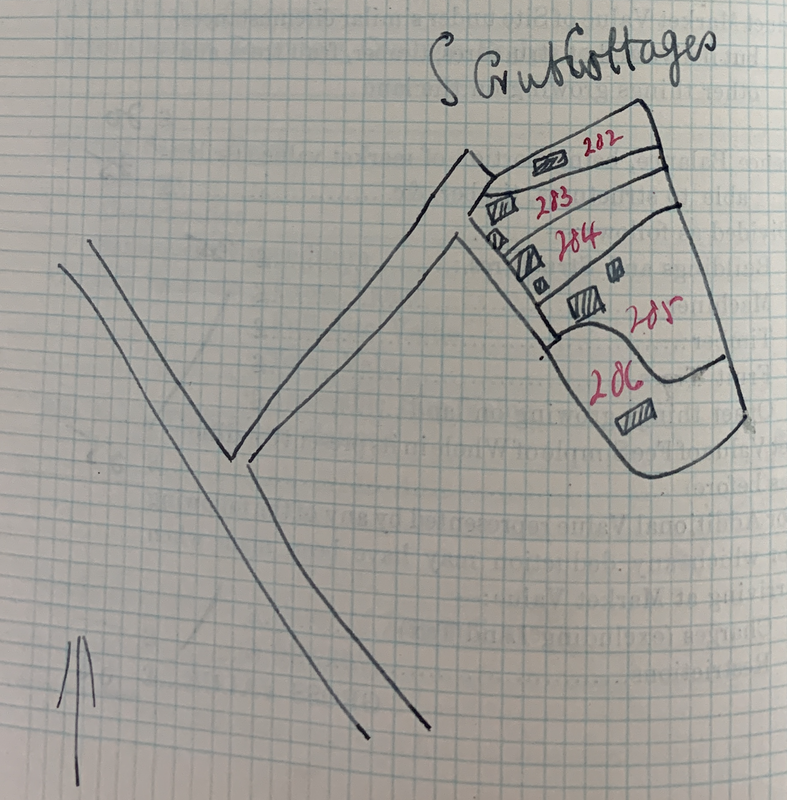

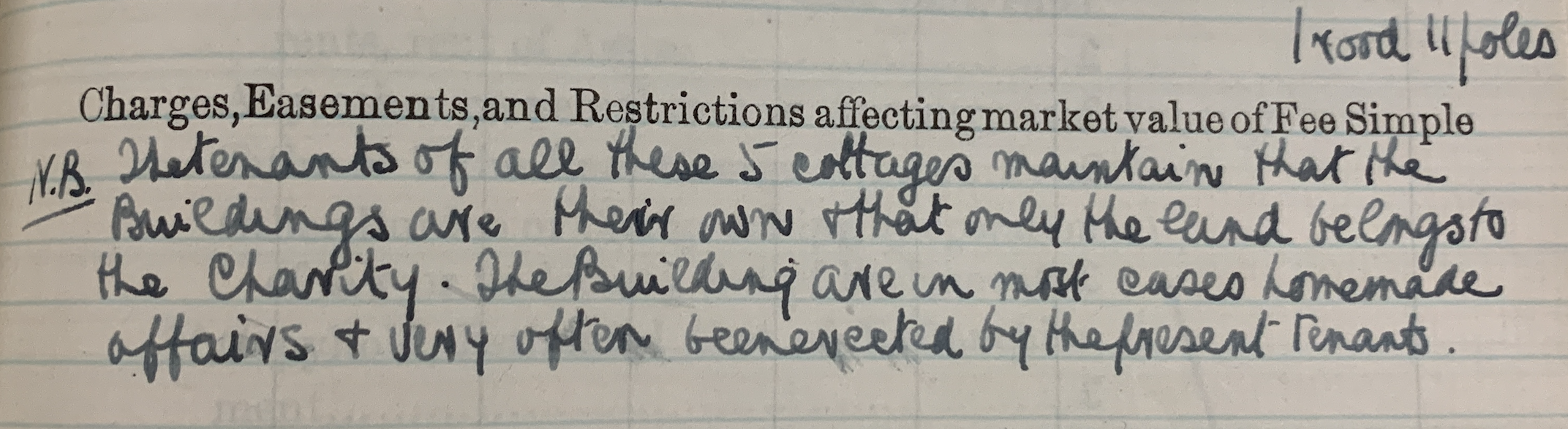

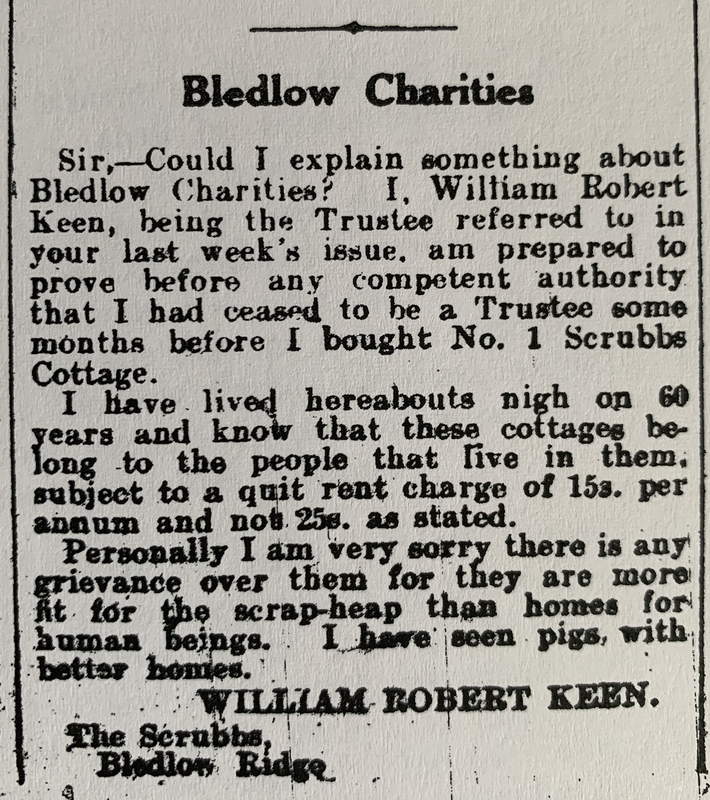

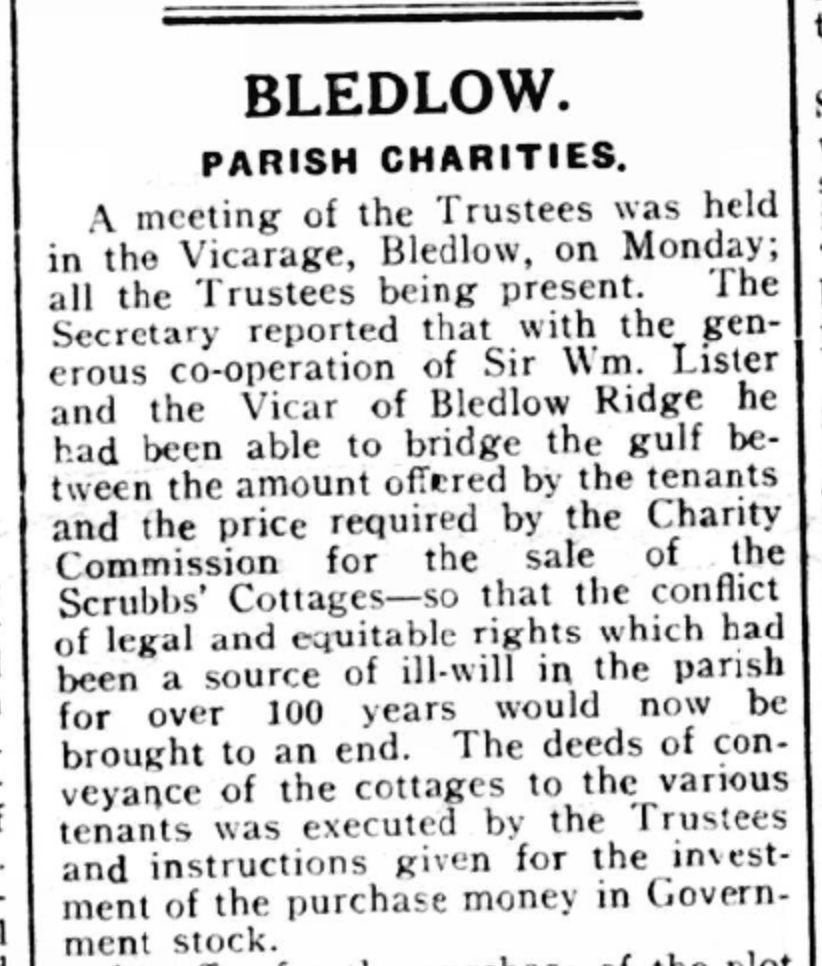

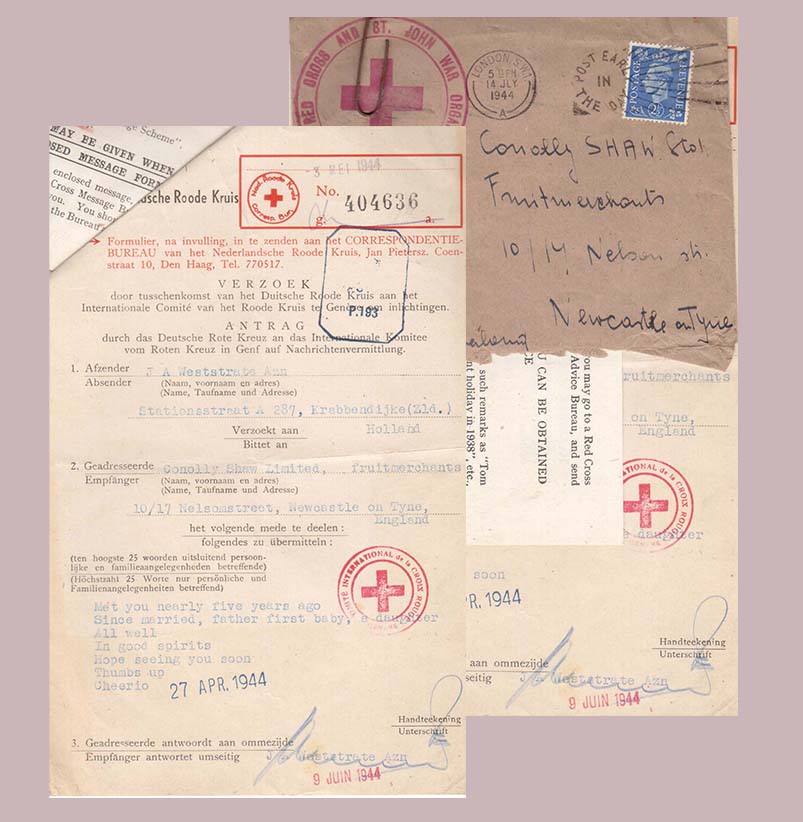

Colony Cottages - Ownership Dispute:

283 - Mrs Brooks

284 - Newell

285 - Isaac Brooks

286 - James Brooks

No. 3 Scrubbs Cottages, Bledlow Ridge, Mr G. A. Smith

No. 4 Scrubbs Cottages, Bledlow Ridge, Mr Owen East [22]

Footnotes:

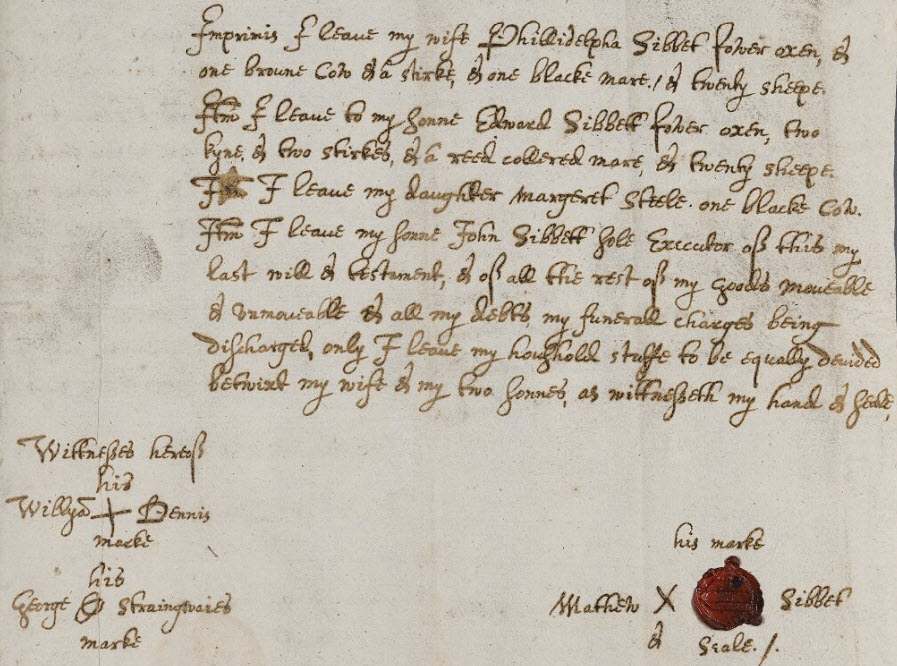

[2] Bleldow Parish Records; Charity and Schools [Bledlow], ‘A book of the wills of benefactors and of other writings relating to the parish of Bledlow, 1768', 1768, 1800-1831, PR_17/25/2, Buckinghamshire Archives.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The Buckinghamshire Village Book, Buckinghamshire Federation of Women’s Institutes, Countryside Books, 1987, p.19.

[7] Oakley, Gwen, Bledlow Ridge, 1973.

[8] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14; Public Charities, Analytical Digest of the Commissioners’ Reports, In Continuation of Digest Printed in 1832, London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1835, p.16.

[9] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14.

[10] 'Charity book' [accounts of payments to the poor] [Bledlow], 1702-1759, 1830-1853, PR_17/25/1, Buckinghamshire Archives.

[11] Bledlow Ridge Board School in 1915, Photograph and Article, Newspaper Cutting in possession of author.

[12] 'Charity book' [accounts of payments to the poor] [Bledlow], 1702-1759, 1830-1853, PR_17/25/1, Buckinghamshire Archives.

[13] Over-Crowding at Bledlow Ridge, Typed copy of article from Bucks Free Press, September 1896, email from Mary Anne Britnell, 17th September 2000, copy in possession of author.

[14] A BLEDLOW RIDGE CASE, The Bucks Herald, 15th April 1911, p. 3, col. 2-3

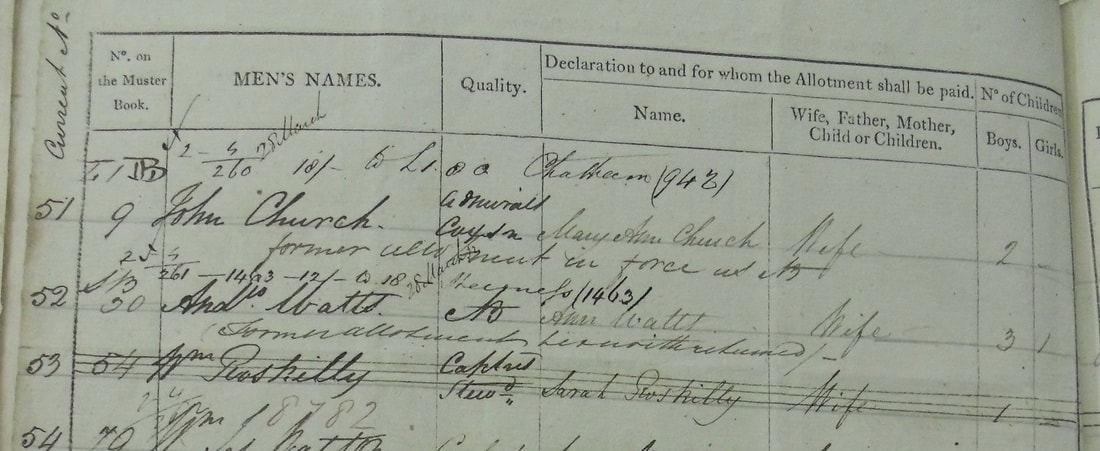

[15] Board of Inland Revenue: Valuation Office: Field Books, Bledlow Assessment No. 201-200, IR 58/39387, No. 282, The National Archives

[16] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14.

[17] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.10.

[18] Bledlow Charities Dispute, Vicar’s Action Defended at Parish Meeting, Bucks Free Press, 6th February 1931.

[19] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14.

[20] "Former miller, Bledlow Ridge, Bucks - Mr Keen?”, VENN-IMG-01-023, The Mills Archive, available at: https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/former-miller-bledlow-ridge-bucks-mr-keen, accessed: 22nd August 2022.

[21] McGown, Melville, op. cit., pp.14-15.

[22] Demolition Orders, Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, Princes Risborough “Advertiser”, 6th September 1935, p.2, col. 3.

[23] HOUSING SITES, The Bucks Herald, 6th September 1935, p.15, col. 5.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed