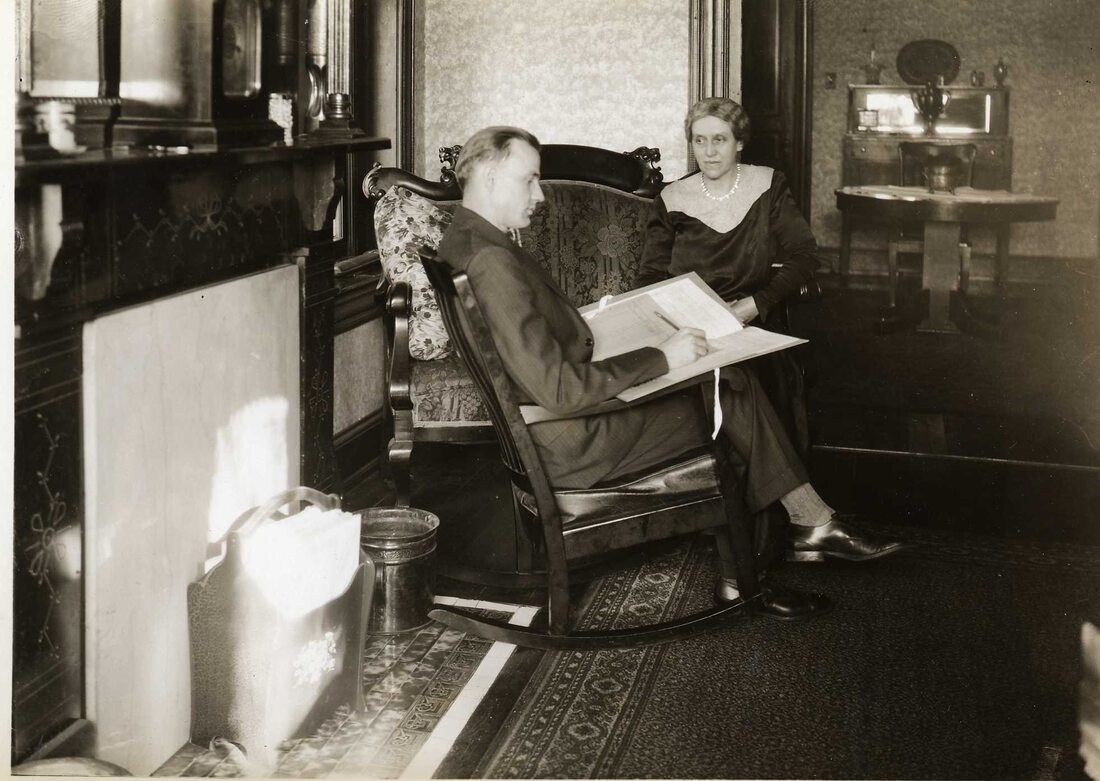

The enumerators were selected for their local knowledge, intelligence, education, reliability and respectability. The role of the enumerator was to deliver to each household a Householder’s Schedule, with written instructions on how the form was to be completed. The head of the household was required, by law, to complete the form on the Sunday night of the census, detailing all those persons who were sleeping in the house that night. Night-workers who were away working, but would be returning to the household that morning to sleep, were also to be listed. Special forms were supplied for asylums, hospitals, schools and similar institutions with over 100 occupants. The enumerator returned the following day and collected the Householder’s Schedule and they checked the contents for discrepancies and clarified anything they did not understand, or helped the householder to complete the Schedule, for example if they could not read or write.

Once all the Householder’s Schedules were collected, the enumerator entered all the particulars in the Census Enumerator’s Book and it is these books that we regularly search on sites such as Ancestry and FindMypast. Both sets of documents were then submitted for checking and examination by the district registrar before they were sent to the Census Office in the General Register Office in London. There they were again checked, and with a few exceptions for the 1841 – 1901 census, the Householders’ Schedules were then destroyed. The exception being the 1911 census Householders’ Schedules, which have been retained.

The data provided was then analysed and recorded in a series of tables as a final Census report. We sometimes forget that the population Census was actually taken for a reason and that it wasn’t actually intended to be used for genealogy purposes! The information taken during the census was used by the Government to plan public funded services including healthcare, housing, education and transport. Under the Hundred Year rule, the data was and still is inaccessible to the general public for 100 years, but after that, it becomes a treasure trove for anyone tracing their family tree.

There was also specific definitions that the Enumerator’s had to adhere, for example:

- A household is defined as: “One person living alone, or a group of people (who do not have to be related) living at the same address who share cooking facilities and share a living room or sitting room or dining area”.

- A householder is defined as:

- “A person who usually lives at this address and, on their own or with someone else: owns or rents the accommodation, and/or pays the household bills and expenses”

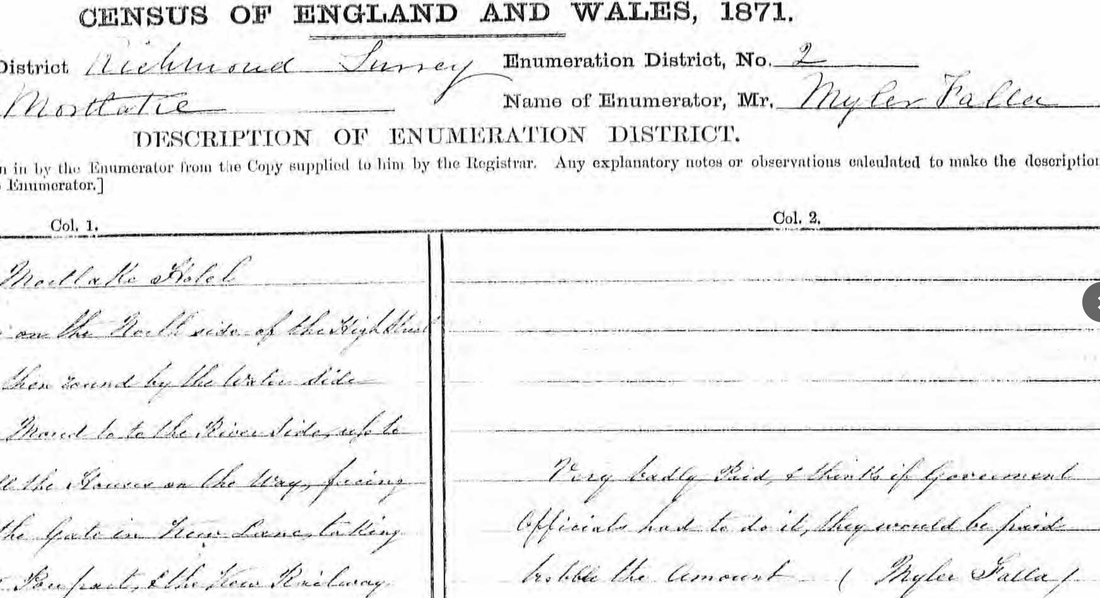

Whilst it’s fantastic that all the Census records are now available online, taking things into context is vital when studying the lives of our ancestors. It’s far to easy to grab the image that you were searching for, add those details to your tree and move onto the next one. If you can, time permitting, you should always look at your ancestors neighbours, look at neighboring streets on the pages either side, were there any common occupations amongst them? What were the living conditions like, are we talking about a cramped two up, two down terraced house, or maybe a more middle class suburban life? Ask yourself these questions and you can quickly learn about the social context in which your ancestors lived. Are we in a rural location with agricultural labourers a plenty? By posing these questions and using the information from the adjacent pages of the census, you can quite quickly get a “feel” for the life that your ancestor was leading. I always check the first and last pages of a registration district schedule as well, sometimes you might find some additional notes made by the enumerator at the time, which can give you a real insight into the task he was undertaking and the area that your ancestor lived. Take time to understand the abbreviations used in the schedules, MS = Male Servant., FS = Female Servant and IND = Independent means are just a few examples. Also the definition of a border is different to that of a lodger, so you will gain more from your results if you understand the roles and terminology. I urge you next time to walk the whole route with the enumerator, follow the whole schedule, ideally whilst looking at a relevant map.

A large quantity of maps are available to view online at the National Library of Scotland website. NLS Website It’s by comparing the two side by side, that you get a much more rounded view of the place your ancestor lived and the role of the enumerator itself.

If you understand more about the role of the enumerator itself, it can also help you understand how easily your ancestor might have slipped through the net. Although in reality, not many actually did slip through the net, it’s more a case of transcription errors and people turning up in the places that you didn’t expect. On a ship for example, in a hospital, institution, or workhouse, where in many cases individuals were only listed by their initials. A lot of the times, the accuracy and the amount of effort that went into the finished article, that we search online, depended on the integrity of the individual enumerators in the area that you are researching. Local accents will always sway what is finally recorded, in a similar way to the early parish registers’s, an enumerator could only write what he thought he heard, if the head of the household could not read or write. So bear in mind local dialect and accents when carrying out your searches. A reason for a missing ancestor from a census return could be varied, but the most likely explanation is that they are there, but you just can’t find them, but that’s whole different story.

Census The Family Historian’s Guide Published by The National Archives link available below

Census The Family Historian’s Guide

There there are many great examples, but I have chosen this particular entry for Mortlake in 1871 and this is viewable on the major websites and can be found at the start of the enumerator’s schedule.

“Very badly paid. I think if Government Officials had to do it, they would be paid treble the amount”

A Census Enumerator approached the house of Mrs Karen Mills. After asking her a series of questions and taking down her replies, he asked her age. She chuckled bashfully and replied, “have you asked the Hills family next door?” “No” was his confused reply. ” I’m about as old as them” she told the Enumerator.

The next week she went to check her updated details and she saw this

Name: Karen Mills

Age : As old as the hills

Be careful of what you say………..

Further reading why not try Peter Christian and David Annal’s Census: The Family Historian’s Guide and Emma Jolly’s Tracing Your Ancestors Using the Census (Pen & Sword) both packed with lots of helpful information and books that every aspiring Family History Researcher should have in their collection.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed