by CAROLINE BROWN, PROGRAMME LEADER ARCHIVES AND

FAMILY HISTORY, CAIS, UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE.

Introduction

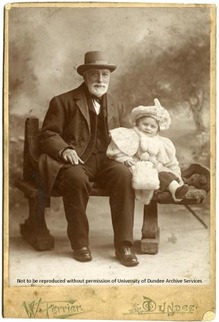

Making a Skeleton Dance

In all of us there is a hunger, marrow deep, to know our heritage - to know who we are and where we came from. Without this enriching knowledge, there is a hollow yearning. No matter what our attainments in life, there is still a vacuum, an emptiness, and the most disquieting loneliness. -- Alex Haley, Roots

| You will not be the only person with memories of that event, and your shared memories will link you together. These links may be particularly strong, such as those between families or communities, and these memories and links are part of what contributes to your (or your family’s) sense of identity. It may even be that the act of creating and bringing together archives and artefacts of your life, and of your ancestors, instigates or reinforces that identity. Without this comes the yearning and emptiness that Haley speaks of. |

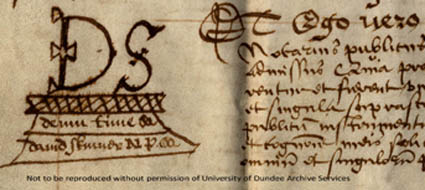

- Archives are evidence. Do you know whether what you are looking at is reliable? Is it authentic? What has happened to it since it was created.

- It is important to remember that everyone brings different memories, backgrounds, experiences and expectations to archives, and may go away with very different interpretations.

- Archives are not the past. It is as important to remember what hasn’t survived or what wasn’t created as it is to understand what does exist.

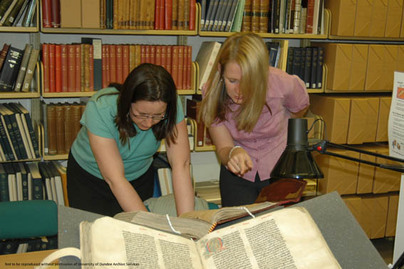

- Digital records might be great, but nothing beats handling (or even smelling!) originals.

Links

http://www.dundee.ac.uk/cais/programmes/discoverexploreyourfamilyandlocalhistory/

http://www.ancestryhour.co.uk/register-for-live-qa-with-university-of-dundee-cais-16th-july.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed